⟞ Exhibit Menu ⟝

The ILGWU

Social Unionism in Action

Little Rock

The Kellwood strike in Little Rock Arkansas in 1966–1967 was one such case. It was a strike little noticed at the time, and even less well remembered today, and yet it was a remarkable example of an organizing drive and strike that crossed deeply entrenched racial barriers.

The Kellwood strike in Little Rock Arkansas in 1966–1967 was one such case. It was a strike little noticed at the time, and even less well remembered today, and yet it was a remarkable example of an organizing drive and strike that crossed deeply entrenched racial barriers.

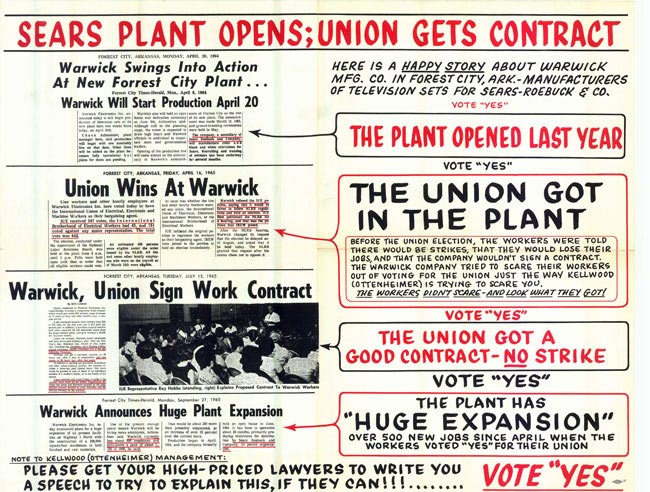

Efforts had been made to organize the workers who manufactured dresses, blouses, and bathrobes in the largest garment factory in Little Rock off and on since 1946, with little success. By the 1960s two old Oppenheimer factories—one employing black workers and the other employing white workers—had been relocated into a new building, with segregation still firmly in place. However, although the black workers still had to endure many discriminatory measures, all the workers were at the mercy of the new corporate owners—Kellwood. a Fortune 500 company and a major supplier for Sears, Roebuck & Co.

Complaints from workers, both black and white, stimulated a union organizing drive, which was met with an intense union-busting campaign on the part of management. However, the union’s strategy in response was unusual and took management by surprise. Instead of calling for desegregation, the ILGWU made sure that each union committee comprised an equal number of black and white workers. It also organized an interracial choir. A committee of “ladies from Little Rock” (five white and five black) traveled to New York City to publicize the strike.

A high point of the campaign came when, nine months into the strike, Little Rock’s labor organizations joined the ILGWU for a mass march through the city to the steps of the state capitol. There the Governor, Winthrop Rockefeller, assured the crowd he would try to settle the strike, whereupon the interracial choir led the crowd in singing “We Shall Overcome.”

Not surprisingly, the strike’s ending, like the rest of the story, was complex. After a 13 month strike, the workers returned to work without a contract, but having initiated a complaint in court. Four long years later they won their case in the courts. Although the contract was renewed every three years thereafter, the company remained fiercely anti-union. By the late 1970s, it began moving work to Haiti and other offshore plants, finally closing the Little Rock factory in 1984.

Not surprisingly, the strike’s ending, like the rest of the story, was complex. After a 13 month strike, the workers returned to work without a contract, but having initiated a complaint in court. Four long years later they won their case in the courts. Although the contract was renewed every three years thereafter, the company remained fiercely anti-union. By the late 1970s, it began moving work to Haiti and other offshore plants, finally closing the Little Rock factory in 1984.

The union did have the satisfaction of compelling the company to sign an agreement in which the two sides pledged to honor each other’s “human dignity,” no small accomplishment when negotiated with a company with such long-standing discriminatory practices.

Labor historian Jon Bloom contributed most of the information for this portion of the exhibit. More detail can be found in his article “The Kellwood Strike of 1966-1967: an Unknown Civil Rights Victory,” (NYLHA News Service, 1988).

We present here a selection of flyers produced during the strike, notable for their sophisticated approach to the local situation—flyers that almost speak to each other—from both the union builders and the union busters.